MORE FREE TERM PAPERS MANAGEMENT:

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

VALUE BASED MANAGEMENT

What is Value - Based Management?

RECENT YEARS HAVE SEEN a plethora of new management approaches for improving organizational performance: total quality management, flat organizations, empowerment, continuous improvement, reengineering, kaizen, team building, and so on. Many have succeeded – but quite a few have failed. Often the cause of failure was performance targets that were unclear or not properly aligned with the ultimate goal of creating value. Value-based management (VBM) tackles this problem head on. It provides a precise and unambiguous metric – value – upon which an entire organization can be built.

The thinking behind VBM is simple. The value of a company is determined by its discounted future cash flows. Value is created only when companies invest capital at returns that exceed the cost of that capital. VBM extends these concepts by focusing on how companies use them to make both major strategic and everyday operating decisions. Properly executed, it is an approach to management that aligns a company’s overall aspirations, analytical techniques, and management processes to focus management decision making on the key drivers of value.

Principles

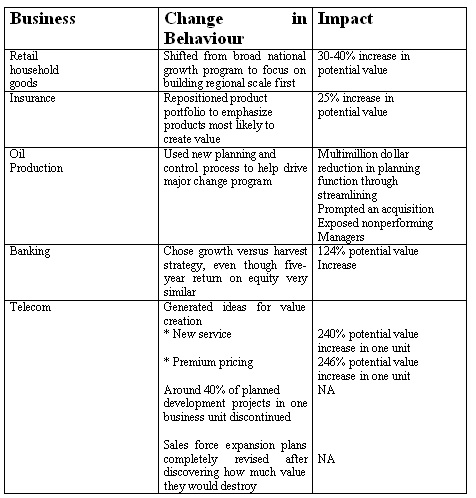

VBM is very different from 1960s-style planning systems. It is not a staff driven exercise. It focuses on better decision making at all levels in an organization. It recognizes that top-down command-and-control structures cannot work well, especially in large multi business corporations. Instead, it calls on managers to use value-based performance metrics for making better decisions. It entails managing the balance sheet as well as the income statement, and balancing long- and short-term perspectives. When VBM is implemented well, it brings tremendous benefit. It is like restructuring to achieve maximum value on a continuing basis. It works. It has high impact, often realized in improved economic performance, as illustrated in Exhibit 1.

Examples of VBM’s impact: Exhibit-1

Pitfalls

Yet value-based management is not without pitfalls. It can become a staff-captured exercise that has no effect on operating managers at the front line or on the decisions that they make.

A few years ago, the chief planning officer of a large company gave us a preview of a presentation intended for his chief financial officer and board of directors. For about two hours we listened to details of how each business unit had been valued, complete with cash flow forecasts, cost of capital, separate capital structures, and the assumptions underlying the calculations of continuing value. When the time came for us to comment, we had to give the team A+ for their valuation skills. Their methodology was impeccable. But they deserved an F for management content.

None of the company’s significant strategic or operating issues were on the table. The team had not even talked to any of the operating managers at the group or business-unit level. Scarcely relevant to the real decision makers, their presentation was a staff-captured exercise that would have no real impact on how the company was run. Instead of value-based management, this company simply had value veneering.

Not methodology

The focus of VBM should not be on methodology. It should be on the why and how of changing your corporate culture. A value-based manager is as interested in the subtleties of organizational behaviour as in using valuation as a performance metric and decision-making tool.

When VBM is working well, an organization’s management processes provide decision makers at all levels with the right information and incentives to make value-creating decisions. Take the manager of a business unit. VBM would provide him or her with the information to quantify and compare the value of alternative strategies and the incentive to choose the value-maximizing strategy. Such an incentive is created by specific financial targets set by senior management, by evaluation and compensation systems that reinforce value creation, and – most importantly – by the strategy review process between manager and superiors. In addition, the manager’s own evaluation would be based on long- and short-term targets that measure progress toward the overall value creation objective.

VBM operates at other levels too. Line managers and supervisors, for instance, can have targets and performance measures that are tailored to their particular circumstances but driven by the overall strategy. A production manager might work to targets for cost per unit, quality, and turnaround time. At the top of the organization, on the other hand, VBM informs the board of directors and corporate centre about the value of their strategies and helps them to evaluate mergers, acquisitions, and divestitures.

Value-based management can best be understood as a marriage between a value creation mindset and the management processes and systems that are necessary to translate that mindset into action. Taken alone, either element is insufficient. Taken together, they can have a huge and sustained impact.

A value creation mindset means that senior managers are fully aware that their ultimate financial objective is maximizing value; that they have clear rules for deciding when other objectives (such as employment or environmental goals) outweigh this imperative; and that they have a solid analytical understanding of which performance variables drive the value of the company. They must know, for instance, whether more value is created by increasing revenue growth or by improving margins, and they must ensure that their strategy focuses resources and attention on the right option.

Management processes and systems encourage managers and employees to behave in a way that maximizes the value of the organization. Planning, target setting, performance measurement, and incentive systems are working effectively when the communication that surrounds them is tightly linked to value creation.

The value mindset

The first step in VBM is embracing value maximization as the ultimate financial objective for a company. Traditional financial performance measures, such as earnings or earnings growth, are not always good proxies for value creation. To focus more directly on creating value, companies should set goals in terms of discounted cash flow value, the most direct measure of value creation. Such targets also need to be translated into shorter-term, more objective financial performance targets.

Companies also need nonfinancial goals – goals concerning customer satisfaction, product innovation, and employee satisfaction, for example – to inspire and guide the entire organization. Such objectives do not contradict value maximization. On the contrary, the most prosperous companies are usually the ones that excel in precisely these areas. Nonfinancial goals must, however, be carefully considered in light of a company’s financial circumstances. A defence contractor in the United States, where shrinkage is a certainty, should not adopt a “no layoffs” objective, for example.

Objectives must also be tailored to the different levels within an organization. For the head of a business unit, the objective may be explicit value creation measured in financial terms. A functional manager’s goals could be expressed in terms of customer service, market share, product quality, or productivity. A manufacturing manager might focus on cost per unit, cycle time, or defect rate. In product development, the issues might be the time it takes to develop a new product, the number of products developed, and their performance compared with the competition.

Even within the realm of financial goals, managers are often confronted with many choices: boosting earnings per share, maximizing the price/earnings ratio or the market-to-book ratio, and increasing the return on assets, to name a few. We strongly believe that value is the only correct criterion of performance.

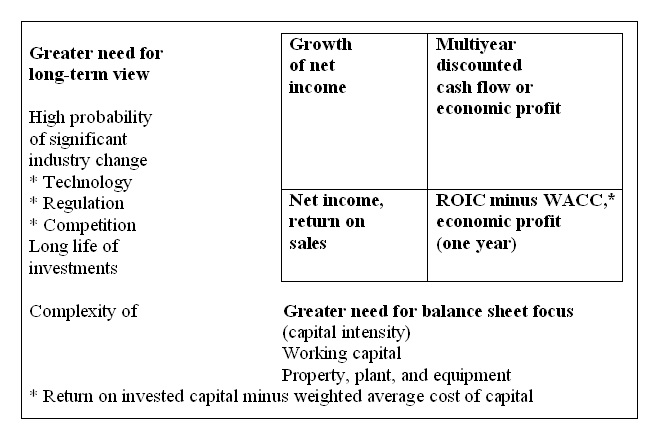

Exhibit 2 compares various measures of corporate performance along two dimensions: the need to take a long-term view and the need to manage the company’s balance sheet. Only discounted cash flow valuation handles both adequately. Companies that focus on this year’s net income or on return on sales are myopic and may overlook major balance sheet opportunities, such as working capital improvement or capital expenditure efficiency.

Measuring Corporate Performance: Exhibit-2

Decision making can be heavily influenced by the choice of a performance

metric. Shifting to a value mindset can make an enormous difference. Real-life

cases that show how focusing on value can transform decision making are

described in the inserts “VBM in action.”

Finding the value drivers

An important part of VBM is a deep understanding of the performance variables that will actually create the value of the business – the key value drivers. Such an understanding is essential because an organization cannot act directly on value. It has to act on things it can influence – customer satisfaction, cost, capital expenditures, and so on. Moreover, it is through these drivers of value that senior management learns to understand the rest of the organization and to establish a dialogue about what it expects to be accomplished.

A value driver is any variable that affects the value of the company. To be useful, however, value drivers need to be organized so that managers can identify which have the greatest impact on value and assign responsibility for them to individuals who can help the organization meet its targets.

Value drivers must be defined at a level of detail consistent with the decision variables that are directly under the control of line management. Generic value drivers, such as sales growth, operating margins, and capital turns, might apply to most business units, but they lack specificity and cannot be used well at the grass roots level. Value drivers can be useful at three levels: generic, where operating margins and invested capital are combined to compute ROIC; business unit, where variables such as customer mix are particularly relevant; and grass roots, where value drivers are precisely defined and tied to specific decisions that front-line managers have under their control.

It took five levels of detail to reach useful operational value drivers. The “span of control,” for example, was defined as the ratio of supervisors to workers. A small improvement here had a big impact on the value of the company without affecting the quality of customer service. Percent occupancy is the fraction of total work hours that are spent at an operator station. Relatively minor changes here also have a major impact on value.

Key value drivers are not static; they must be regularly reviewed. Once the retailer reaches its goal of 1.2 delivery trips per transaction, for example, it may need to shift its focus to cost per trip (while continuing to monitor trips per transaction to make sure it stays on target).

Identifying key value drivers can be difficult because it requires an organization to think about its processes in a different way. Often, too, existing reporting systems are not equipped to supply the necessary information. Mechanical approaches based on available information and purely financial measures rarely succeed. What is needed instead is a creative process involving much trial and error.

Nor can value drivers be considered in isolation from each other. A price increase might, taken alone, boost value – but not if it results in substantial loss of market share. In seeking to understand the interrelationships among value drivers, scenario analysis is a valuable tool. It is a way of assessing the impact of different sets of mutually consistent assumptions on the value of a company or its business units. Typical scenarios include what might happen if there is a price war, or if additional capacity comes on line in another country? Thinking about such issues helps management avoid getting caught off guard and brings to life the relationship between strategy and value.

Management processes

Adopting a value-based mindset and finding the value drivers gets you only halfway home. Managers must also establish processes that bring this mindset to life in the daily activities of the company. Line managers must embrace value-based thinking as an improved way of making decisions. And for VBM to stick, it must eventually involve every decision maker in the company.

There are four essential management processes that collectively govern the adoption of VBM. First, a company or business unit develops a strategy to maximize value. Second, it translates this strategy into short- and long-term performance targets defined in terms of the key value drivers. Third, it develops action plans and budgets to define the steps that will be taken over the next year or so to achieve these targets. Finally, it puts performance measurement and incentive systems in place to monitor performance against targets and to encourage employees to meet their goals.

These four processes are linked across the company at the corporate, business-unit, and functional levels. Clearly, strategies and performance targets must be consistent right through the organization if it is to achieve its value creation goals.

Strategy development

Though the strategy development process must always be based on maximizing value, implementation will vary by organizational level.

At the corporate level, strategy is primarily about deciding what businesses to be in, how to exploit potential synergies across business units, and how to allocate resources across businesses. In a VBM context, senior management devises a corporate strategy that explicitly maximizes the overall value of the company, including buying and selling business units as appropriate. That strategy should be built on a thorough understanding of business-unit strategies.

At the business-unit level, strategy development generally entails identifying alternative strategies, valuing them, and choosing the one with the highest value. The chosen strategy should spell out how the business unit will achieve a competitive advantage that will permit it to create value. This explanation should be grounded in a thorough analysis of the market, the competitors, and the unit’s assets and skills. The VBM elements of the strategy then come into play. They include:

• Assessing the results of the valuation and the key assumptions driving the value of the strategy. These assumptions can then be analyzed and challenged in discussions with senior management.

• Weighing the value of the alternative strategies that were discarded, along with the reasons for rejecting them.

• Stating resource requirements. VBM often focuses business-unit managers on the balance sheet for the first time. Human resource requirements should also be specified.

• Summarizing the strategic plan projections, focusing on the key value drivers. These should be supplemented by an analysis of the return on invested capital over time and relative to competitors.

• Analyzing alternative scenarios to assess the effect of competitive threats or opportunities.

Developing business-unit strategy does not have to become a bureaucratic time sink; indeed, the time and costs associated with planning can even be reduced if VBM is introduced simultaneously with a reengineering of the planning process.

Target setting

Once strategies for maximizing value are agreed, they must be translated into specific targets. Target setting is highly subjective, yet its importance cannot be overstated. Targets are the way management communicates what it expects to achieve. Without targets, organizations do not know where to go. Set targets too low, and they may be met, but performance will be mediocre. Set them at unattainable levels, and they will fail to provide any motivation.

In applying VBM to target setting, several general principles are helpful:

Base your targets on key value drivers, and include both financial and nonfinancial targets. The latter serve to prevent “gaming” of short-term financial targets. An R&D-intensive company, for example, might be able to improve its short-term financial performance by deferring R&D expenditures, but this would detract from its ability to remain competitive in the long run. One solution is to set a nonfinancial goal, such as progress toward specific R&D objectives that supplements the financial targets.

Tailor the targets to the different levels within an organization. Senior business-unit managers should have targets for overall financial performance and unit-wide nonfinancial objectives. Functional managers need functional targets, such as cost per unit and quality.

Link short-term targets to long-term ones. An approach we particularly like is to set linked performance targets for ten years, three years, and one year. The ten-year targets express a company’s aspirations; the three-year targets define how much progress it has to make within that time in order to meet its ten-year aspirations; and the one-year target is a working budget for managers. Ideally, you should always set targets in terms of value, but since value is always based on long-term future cash flows and depends on an assessment of the future, short-term targets need a more immediate measure derived from actual performance over a single year. Economic profit is a short-term financial performance measure that is tightly linked to value creation. It is defined as:

Economic profit =

Invested capital x (Return on invested capital – Weighted average cost

of capital)

Economic profit measures the gap between what companies earns during a period and the minimum it must earn to satisfy its investors. Maximizing economic profit over time will also maximize company value.

Action plans and budgets

Action plans translate strategy into the specific steps an organization will take to achieve its targets, particularly in the short term. The plans must identify the actions that the organization will take so that it can pursue its goals in a methodical manner.

Performance measurement

Performance measurement and incentive systems track progress in achieving targets and encourage managers and other employees to achieve them. Rarely do front-line supervisors and employees have clear performance measures that are linked to their company’s long-term strategy; indeed, many have none at all.

VBM may force a company to modify its traditional approach to these systems. In particular, it shifts performance measurement from being accounting driven to being management driven. All the same, developing a performance measurement system is relatively straightforward for a company that understands its key value drivers and has set its short- and long-term targets. Key principles include:

1. Tailor performance measurement to the business unit. Each business unit should have its own performance measures – measures it can influence. Many multi business companies try to use generic measures. They end up with purely financial measures that may not tell senior management what is really going on or allow for valid comparisons across business units. One unit might be capital intensive and have high margins, while another consumes little capital but has low margins. Comparing the two on the basis of margins alone does not tell the full story.

2. Link performance measurement to a unit’s short- and long-term targets. This may seem obvious, but performance measurement systems are often based almost exclusively on accounting results.

3. Combine financial and operating performance in the measurement.

Too often, financial performance is reported separately from operating

performance, whereas an integrated report would better serve managers’

needs.

4. Identify performance measures that serve as early warning indicators. Financial indicators can only measure what has already happened, when it may be too late to take corrective action. Early warning indicators might be simple items such as market share or sales trends, or more sophisticated pointers such as the results of focus group interviews.

Once performance measurements are an established part of corporate culture and managers are familiar with them, it is time to revise the compensation system. Changes in compensation should follow, not lead, the implementation of a value-based management system.

Compensation design

The first principle in compensation design is that it should provide the incentive to create value at all levels within an organization. Compensation for the chief executive officer – though a popular topic in the press – is something of a red herring. Managers’ performance should be evaluated by a combination of metrics that reflects their organizational responsibilities and control over resources.

At the chief executive level in a publicly-held company, increases in stock prices are directly observable, and therefore a CEO’s bonus can take the form of stock options or stock appreciation rights. Even so, many stock price changes result from factors outside the CEO’s control, such as falls in interest rates. Stock appreciation plans can, however, be adjusted to remove such general market influences so that they focus on the aspects of company performance that are directly attributable to the skill of top management.

Discounted cash flow (DCF) is not one of the performance metrics in Exhibit 6 for good reasons. DCF is the present value of forecasted cash flows. If compensation relied on DCF, it would be based on projections, not results.

However, we do recommend using DCF in conjunction with economic profit

to establish benchmarks and reward performance at the business-unit level.

The long-term perspective provided by DCF can balance the short-term,

accounting-based metric of economic profit. The latter is often negative

in, for example, start-up or turnaround projects, even though value is

being created.

The role of DCF is to act as a corrective so that compensation can be

calculated appropriately at the business-unit level.

At the front line of management, where financial information is rarely an adequate guide, operating value drivers are the key. They must be sufficiently detailed to be tied to the everyday operating decisions that managers have under their control.

Implementing VBM successfully

Although putting a VBM system in place is a long and complex process, successful efforts share a number of common features (see Exhibit-3). Most of these points have already been discussed, and others are self-explanatory, but the first feature is worth elaborating.

Keys to successful implementation: Exhibit-3

1. Establish explicit, visible top management support.

2. Focus on better decision making among operating (not just financial)

personnel.

3. Achieve critical mass by building skills in a wide cross-section of

the company.

4. Tightly integrate the VBM approach with all elements of planning.

5. Underemphasize methodological issues and focus on practical applications.

6. Use strategic issue analyses that are tailored to each business unit

rather than a generic approach.

7. Ensure the availability of crucial data (e.g. business-unit balance

sheets).

8. Provide standardized, easy-to-use valuation templates and report formats

to facilitate the submission of management reports.

9. Tie incentives to value creation.

10. Require that capital and human resource requests be value based.

As with any major program of organizational change, it is vital for top

management to understand and support the implementation of VBM. At one

company, the CEO and CFO made a video for their employees in whom they

pledged their support for the initiative declared that the basis of compensation

would shift at the end of the year from earnings to economic profit, and

gave examples of what VBM meant. All business units, for instance, would

be expected to earn their cost of capital. “If our cost of capital is

12 percent,” the CEO said, “a 12 percent rate of return on the capital

that we have invested is not good enough. An 11 percent return destroys

value, and a 13 percent return creates value. But a 14 percent rate of

return creates twice as much value as a 13 percent return.”

Most managers had not thought about their business in these terms. The

video caught their attention and showed them that top management supported

the change that was under way.

Though active top management support is a necessary condition for the successful implementation of VBM, it is not sufficient in itself. Value-based management, as we have suggested, must permeate the entire organization. Not until line managers embrace VBM and use it on a daily basis for making better decisions can it achieve its full impact as an aid to the long-term maximization of value.

Conclusion

Although putting a VBM system in place is a long and complex process, successful efforts share a number of common features. Most of these points have already been discussed, and others are self-explanatory, but the first feature is worth elaborating.

Most managers had not thought about their business in these terms. The video caught their attention and showed them that top management supported the change that was under way.

Though active top management support is a necessary condition for the successful implementation of VBM, it is not sufficient in itself. Value-based management, as we have suggested, must permeate the entire organization. Not until line managers embrace VBM and use it on a daily basis for making better decisions can it achieve its full impact as an aid to the long-term maximization of value.